MEMORIES OF MAY

MEMORIES OF MAY

By. Will Johnson

Dudley Johnson and Al Hassell here checking the hot springs at Great Hole.

In the month of May 2002, I wrote an article for The Daily Herald. I was in Florida and had a dream in the early morning hours of May 8th. I was in the middle of a volcanic eruption and a silent scream went up towards the heavens. The scream was from at least twenty-eight thousand people being consumed by Mount Pelee, and the lovely city of St. Pierre on Martinique forever to be remembered for her destruction by the angry volcano.

It took me nearly all day before I realized what the dream was all about. It was one hundred years after the destruction. Living for centuries on an active volcano must have seasoned my genes to worry about an eruption.

I was busy writing an article updating the general public as to what if anything is being done to monitor the volcanoes of Saba and Statia. I was quoting from the report of Elske de Zeeuw-van Dalfsen and Reinoud Sleeman which gives a good idea as to what is being done by the Royal Institute of The Netherlands concerned with monitoring weather, and now also volcanoes. It is quite detailed but for the layman it is quite readable. And then just a few days ago there was an article from the Saba Government Information service about a visit from the Institute and giving an update on the equipment they are using and so forth. Given the circumstances and the fact that we are still in the month of May I will incorporate some of the technical details as well as memories of the devastation caused on May 8th, 1902 by the Mt. Pelee on Martinique.

The report made by the Department of Seismology and Acoustics of the Royal Meteorological Institute (KNMI) at the Bilt in The Netherlands reminded me of an incident years ago.

Saint Pierre, had an appeal of a flower that blossomed once only, in one place: that no eye will ever see again.

“Early seismic monitoring on the islands of Saba and St. Eustatius was carried out by the Lamont –Doherty Geological Observatory (U.S.A.) who operated a single one-component seismometer on Saba from 1978 to 1983.”

I remember this site well. It was situated on a then vacant lot next to my house at the edge of the cliff. One afternoon I got a phone call and the man at the other end was out of breath. Practically screaming into the phone asking me:” How are you coping? Is there anyone alive besides you? “Turns out he was calling from the Colombia University in New York City. Somehow they were monitoring this seismometer next to my house. When he told me that there had been a 9 plus magnitude earthquake right under Saba, I assured him that all was well and to hold on a while and I would check the antenna. I checked and came right back and reassured him that indeed all was well and that one of my neighbours had tied his cow to the antenna. So, each time when the cow walked around in search of grass and pulled on the antenna, the equipment was registering earthquakes of more than 9 points magnitude on the Richter scale.”

The extensive report which I was quoiting from for this article has this to say: “As of 1 January 2017, the population of the island of Saba reached 2010 people, and the population of St. Eustatius totaled 3250 people. The expansion of the population at the islands observed over the past decade is expected to continue, implying that the number of people at risk, and the complexity of evacuation in case of volcanic unrest will also increase. The Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI) is responsible for the observations of geophysical phenomena at the islands. In acute potential hazardous situations, KNMI informs local authorities at the islands as well as the departmental crisis coordination center of the Ministry as soon as possible. Responsible agencies on the islands can take further action if needed, assisted by the crisis coordination center. Apart from these potential urgent warnings, KNMI sends the local government a status report 1-2 times a year.

A report from the government information service of Saba of this past week reports the following.

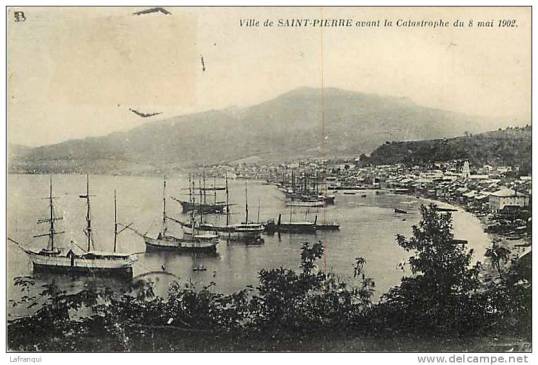

Around 8am Mt. Pelee erupted with such force that the beautiful city of St. Pierre was totally destroyed in a matter of forty five seconds.

“The Department of Seismology and Acoustics of the Royal Netherlands Metrological Institute (KNMI) has been working on Saba for several years to monitor the dormant volcano Mount Scenery. The monitoring of a volcano is best done using multiple techniques to access the state of activity.

One way to monitor is through a so-called Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS). In January 2018, the KNMI installed the first GNSS at St. John’s, followed by a second installation at the Juancho Irausquin Airport in February 2019. Both instruments are operating as expected and data are operating as expected and sent automatically to the KNMI in The Netherlands every hour, using a transmission facilitated by SATEL.

The GNSS instruments have to be regularly maintained to ensure their continued operation. The instruments are subject to harsh environmental conditions: the chloride ions in the air from the evaporated sea salt in ocean spray and the high temperatures speed up the reaction time, corroding even stainless steel. A GNSS instrument measures the distortion of the earth’s surface, making it possible to see whether the surface swells or deflates.

A second way to monitor is through temperature sensors. In January 2018, a temperature sensor was installed at the hot spring opposite Green Island. This sensor takes a measurement every 20 minutes and stores the data locally. The measurements form a time series and stores the data locally. They give more detailed information about temperature changes of the hot spring and is compared to the single measurements that have already been taken.

A second way to monitor is through temperature sensors. In January 2018, a temperature sensor was installed at the hot spring opposite Green Island. This sensor takes a measurement every 20 minutes and stores the data locally. The measurements form a time series and stores the data locally. They give more detailed information about temperature changes of the hot spring and is compared to the single measurements that have already been taken.

If the volcanic activity changes, the temperature of the hot spring can increase. There will also be more fumes. The population is asked when they see fumes or indications of any other possible volcanic activity, to inform the safety coordinator of the Public Entity.

The last visit of the KNMI to the hot spring was in February 2019. Improvements were made to the installation, which includes temperature probes that are buried in the ocean bed and covered with rocks to keep them in place, and data loggers, small yellow cases mounted on the rock above the spring and housed in a black case to protect it against the elements. Due to the high surf activity, it remains to be seen how long the temperature probes and their cables will survive. A more rugged installation is planned for the future.

The third monitoring instrument is the seismometer. The KNMI has installed has installed three seismometers on Saba; in The Bottom, St. John’s and Windward Side. A fourth seismometer will be reinstalled shortly at the airport after the instrument has been repaired. Seismic instruments are important because they record the vibrations of the earth. If a volcano becomes active, the seismic vibrations will intensify, explained De Zeeuw-van Dalfsen. KNMI representatives now visit Saba on a regular basis.

The seismic network is designed to monitor the seismicity in the Caribbean Netherlands region and the seismic signals preceding or accompanying the earthquakes in the region, which may generate tidal waves. The seismic network has been gradually expanded since 2006.

The current monitoring network of Saba is in development. The goal is to enhance the monitoring capability. Future improvements include 1) the installation of a seismic station in the north west area of Saba, 2) the placing of another GNSS station on the island and, 3) installing a more durable temperature sensor which transmits data in real-time to monitor the hot spring on Saba.

So far, this excellent report on the activities of the KNMI.

“My grandmother Agnes Simmons born Johnson (born 1880) told me stories of the morning of May 8th, 1902. They heard two explosions coming from the South. They thought it must be a Dutch man-of-war visiting Statia .

1948. Lt. Governor Max Huith and Police Chief Bernard Halley here checking the hot springs between Tent Bay and the Ladder. They were covered up by a large land slide in recent years, but can still be experienced on the sea bed in the same area.

Captain Irvin Holm (born 1890) who lived on the road to Booby Hill also heard the explosions. He and his brother Captain Ralph as boys were curious to know what was taking place. They walked to the edge of Booby Hill and saw that it was getting dark to the South where the explosions had come from. It got darker as the day went on and ash started to fall on the island. They realized that something had happened but could not imagine how terrible it was. It took almost a week before the news came in. And in that news was included the death of Roland Hassell a mate on a schooner in the harbour of St. Pierre. He was the father of the well-known ‘Bungy’ Hassell from Under the Hill.

I am busy reading for the second time the book ‘The Coloured Countries’ by Alec Waugh. In 1928 he spent several months on the island of Martinique. One day he and his friend Eldred Curwin decided to visit of St. Pierre.

“Once we went to St. Pierre.

From Ford Lahaye it is a three hours’ sail in a canoe, along a coast indented with green valleys that run climbing back climbing through fields of sugar cane.

‘Nor, as you approach Saint Pierre, would you suspect that in that semi-circle of hills under the cloud-hung shadow of Mont Pele, are hidden the ruins of a city for which history can find no parallel.”

‘Nor, as you approach Saint Pierre, would you suspect that in that semi-circle of hills under the cloud-hung shadow of Mont Pele, are hidden the ruins of a city for which history can find no parallel.”

“ But it is not till you have left the town and have climbed to the top of one of the hills, you look down into the basin of Saint Pierre, and, looking down, see through the screen of foliage the outline of house after ruined house, that you realize the extent and nature of the disaster. No place that I have ever seen has moved me in quite that way. At the corners of these streets, men had stood gossiping on summer evenings, watching the sky darken over the unchanging hills, musing on the permanence, the unhurrying continuity of the life they were a part of. It is not that sentiment that makes the sight of Saint Pierre so profoundly solemn. It is the knowledge rather that here existed a life that should be existing still, that existed nowhere else, that was the outcome of a combination of circumstances that now have vanished from the world forever. Even Pompeii cannot give you quite that feeling. It has not that personal, that localized appeal of a flower that has blossomed once only, in one place: that no eye will ever see again.

Saint Pierre was the loveliest city in the West Indies. The loveliest and the gayest. All day its narrow streets were bright with colour; in sharp anglings of light the amber sunshine streamed over the red tiled roofs, the lemon covered walls, the green shutters, the green verandahs. The streets ran steeply, “breaking into steps as streams break into waterfalls.” Moss grew between the stones. In the runnel was the sound of water. There was no such thing as silence in Saint Pierre. There was always the sound of water, of fountains in the hidden gardens, of rain water in the runnels, and through the music of that water, the water that kept the town cool during the long noon heat, came ceaselessly from the hills beyond the murmur of the lizard and the cricket. A lovely city, with its theatre, its lamplit avenues, its’ jardin des plants’, its schooners drawn circle wise along the harbour. Life was comely there; the life that had been built up by the old French emigres. It was a city of carnival. There was a culture there, a love of art among those people who had made their home there, who had not come to Martinique to make money that they could spend in Paris.

Saint Pierre was the loveliest city in the West Indies. The loveliest and the gayest. All day its narrow streets were bright with colour; in sharp anglings of light the amber sunshine streamed over the red tiled roofs, the lemon covered walls, the green shutters, the green verandahs. The streets ran steeply, “breaking into steps as streams break into waterfalls.” Moss grew between the stones. In the runnel was the sound of water. There was no such thing as silence in Saint Pierre. There was always the sound of water, of fountains in the hidden gardens, of rain water in the runnels, and through the music of that water, the water that kept the town cool during the long noon heat, came ceaselessly from the hills beyond the murmur of the lizard and the cricket. A lovely city, with its theatre, its lamplit avenues, its’ jardin des plants’, its schooners drawn circle wise along the harbour. Life was comely there; the life that had been built up by the old French emigres. It was a city of carnival. There was a culture there, a love of art among those people who had made their home there, who had not come to Martinique to make money that they could spend in Paris.

The culture of Versailles was transposed here to mingle with the Carib stock and the dark mysteries of imported Africa. Saint Pierre was never seen without emotion. It laid hold of the imagination. It had something to say, not only to the romantic intellectual like Hearn or Stacpool, but to the sailors and the traders, to all those whom the routine of livelihood brought within the limit of its sway. “Incomparable,” they would say as they waved farewell to the Pays des Revenants, knowing that if they did not return, they would carry all their lives a regret for it in their hearts. And within forty-five seconds the stir and colour of that life had been wiped out. History has no parallel for Saint Pierre.

The culture of Versailles was transposed here to mingle with the Carib stock and the dark mysteries of imported Africa. Saint Pierre was never seen without emotion. It laid hold of the imagination. It had something to say, not only to the romantic intellectual like Hearn or Stacpool, but to the sailors and the traders, to all those whom the routine of livelihood brought within the limit of its sway. “Incomparable,” they would say as they waved farewell to the Pays des Revenants, knowing that if they did not return, they would carry all their lives a regret for it in their hearts. And within forty-five seconds the stir and colour of that life had been wiped out. History has no parallel for Saint Pierre.

Sitting on the walls as a boy and listening to the old captains and sailors who had known and loved this magic city, I became entranced with the Pays des Revenants and have had a lifelong regret that the city was forever lost. Living on a dormant volcano it makes sense to monitor what is going on and glad to share this with the people who have

As can be seen in this photo St. Eustatius and St. Kitts are also dormant volcanoes and for the past years the island of Montserrat has been erupting, cause for alarm on the Dutch Islands as to what is being done about monitoring these volcanoes.

been wondering if anything is being done to monitor our volcano.