PETER HASSELL AND THE REVOLT AGAINST COMMANDER JOHN PHILIPS

PETER HASSELL AND THE REVOLT AGAINST COMMANDER JOHN PHILIPS.

Portrait of Commander John Philips in the National Museum in Holland

Commander John Philips (1733-1746) had done a great job in advancing the economy of St. Maarten. He was also able to accomplish that the island was removed from under the administration of St. Eustatius and became self-governing. He revitalized the salt industry and brought in new settlers and convinced the plantation owners to move away from a subsistence economy to an export economy. The island back then was under the supervision of the Dutch West India company.

All was not well however and he created a number of enemies among them the cantankerous Peter Hassell, born on Saba, and a sugar cane plantation owner in the valley of Cul-de- Sac. The information on Hassell is largely taken from the book by Prof Dr. L. Knappert (Geschiedenis van de Nederlandsche Bovenwindse Eilanden in de 18de eeuw) . This book dates from 1932. I intend to do a separate story on the Dutch historians at some point. Furthermore, from an article by Ph.F.W. van Romondt in the (West Indische Gids of 1941). He was a descendant of Hassell and gave a detailed account of the life and turbulent times of his Saba ancestor.

The name Hassell was spread throughout the Dutch Windwards from early on in the history of European settlement of the islands.

The empty land as it would have looked like in the days of Phillips looking from the valley of Cul-de-Sac to the town in the distance which would be named in his honor.

The islands changed hands frequently between the colonizing European nations in those early years of settlement and people moved around the islands on their own or were forced to move from one island to the next by the various European occupiers. Already in the 17th century the name Hassell can be found on St. Eustatius, St. Maarten and Saba. The first named island (St. Eustatius) was the head island and governed by a Commander while St. Maarten and Saba had to make do with a Vice Commander.

Who are interested in the history of the islands can find much of this from the books in the Dutch language by Hamelberg (De Nederlanders op de West Indische Eilanden), Knappert (Geschiedenis van de Nederlandsche Bovenwiindse Eilanden in de 18de eeuw), and Dr. Johan Hartog who leaned largely on information from both of the previous authors to write his “De Bovenwindse Eilanden).

What follows here is also borrowed from the old archives of Sint Eustatius, Sint Maarten and Saba which are to be found in the Public Records Office in The Hague.

Philips burg from the air in 1955.

Around 1677 Peter Hassell must have been born ,presumably on Saba, and there between 1705 and 1706 he married Susanna Haley, also from Saba. Although Knappert admits that Hassell could not speak a word of Dutch as Saba was an English-speaking island, he still spells the name as Pieter in the Dutch form. From the beginning of our history we English Scottish and Irish descendants have been subjected to Administrators, preachers (Kowan) and other officials who when they could not understand the accent and pronunciation of our ancestral names just took the easy way out and wrote down the name in Dutch as it would have sounded to them. This has been a great source of irritation to those when doing genealogical research.

From the Hassell-Haley marriage five children are known. Jacob born May 14th 1716, Daniel and Helena both born on Saba successively on October 21st, 1718 and July 10th, 1721. The last two Richard and Johannes were born on St. Maarten on January 1st 1724 and May 27th, 1727 (Baptismal book St. Eustatius). The birth place of the first child is unknown. And there should have been other children born between 1706 and 1716 when we find the birth of the first child mentioned here. One can conclude from this information that Peter Hassell and his family moved to Sint Maarten between 1721 and 1723. He can be found there in 1728 when he together with Jan Lespier, citizen and resident of Sint Eustatius, came to an agreement on September 16th, 1728 concerning a sugar plantation in Cul-de-Sac which Hassell would take under his supervision. Seven years later on June 18th 1735, this estate agreement was dissolved. Jan Lespier gave up his share against compensation of 650 pieces of eight. On Hassell’s plantation he

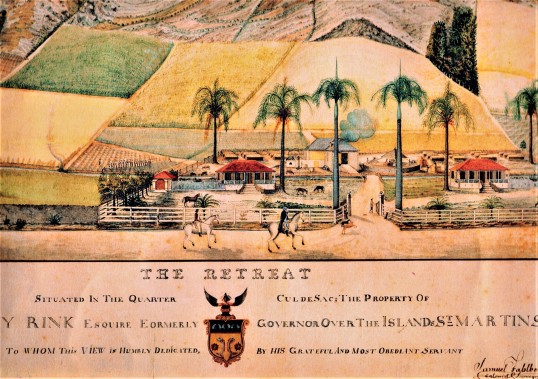

One of the many fine plantations in the valley of Cul=de=Sac

cultivated principally cotton and sugar cane.

On May 7th, 1735 he appears as signatory of a petition for windmills to be used in the salt pans. In a declaration of July 5th, 1729, Peter Hassell is referred to as a ships carpenter. In 1732 (April 16th), the year in which an earthquake struck St. Martin, he is listed as buying a piece of land from William Mussenden.

According to a list of inhabitants of the island of February 28th. 1733 the household of Peter Hassell consisted of the married couple and three sons. From that year on he was a member of council and lieutenant of the civil militia.

When Commander John Philips returned from The Netherlands on February 16th, 1735 to take charge of the island Peter Hassell had just been reelected as a member of council. Philips had convinced the directors of the West India company to give Sint Maarten full autonomy from St. Eustatius. With all of his accomplishment for the island Philips from all accounts was no easy man to deal with. Peter Hassell on the other hand was known as a cantankerous man and was constantly in conflict with others.

Until the late nineteen sixties the town of Philipsburg was still relatively unspoiled.

On Philips return Barry was dismissed but was allowed to stay on island which turned out to be a mistake. Philips’ recorded sins is also not small, and Peter Hassell who shortly after Philips return was elected as a member of council, was one of the many who could not get along with him. Hassell himself was no easy person. There is a report of a complaint made against him for insulting the island secretary of St. Maarten, J.P. Schenk, in which last mentioned expressed his regrets.

In that same year, 1736, the conflict began between Hassell and Philips. This is what happened. Philips had received a letter from the Gentlemen X of October 29th 1735 insisting to collect the head tax. The execution thereof created turmoil among the civilian population and captain Hassell called them to arms, ‘which Philips denied on grounds of rebellion.

The grave of Commander John Philips on the foundation of the first church on St. Maarten located in the Little Bay cemetery. It is supposedly a national monument but I wonder if anyone looks after it or even knows where it is located.

A few months later it got worse. From a declaration by a certain Jan Ryan it appears that he was at the home of the court usher Jan Weyth on June 15th; Philips was also there. Ryan overheard Philips asking Hassell how many governors there were on the island. Hassel answered “one”, but added that he was the captain and could call out the civilian population on their request. Philips then started to curse and confront Hassell. The civilians had restrained them when it threatened to come to blows between the two. Cursing, Philips threatened to banish Hassell from the island, if he had not been banned from Saba. The accusation is not probable as because in the lawsuit against Schenck the magistrate had consulted the court on Saba and was informed that Hassell was known there as an honest man.

Two days later on a Sunday, (June 17th, 1736), because there is talk about leaving the church, Philips was once again by Wyeth. The citizens with Hassell in the lead stormed in the direction of Philips. The captain read off a decree of accusations. Philips denied everything but the citizens shouted “Put him on board” and they took his sword and he was seized and forcefully put on a schooner and brought to St. Thomas. From there he went via St. Eustatius to Holland. The people then proceeded to destroy his house and office, they stole his money, books and papers. Later they arrested his servants and placed them on a diet of bread and water and in the night, they slaughtered his slaves and animals in the fields. In the thirteen months that he was off-island his plantations and warehouses were reduced to ruins, his merchandise was stolen or they spoiled due to lack of air in these warm climates so that his commercial activities came to a halt. His wife Sarah Hartman died from grief. Later Philips described all of this as enough to move even a Turk to sympathy.

Johannes Markoe the Commander of St. Eustatius sent a letter to Holland explaining what had happened with Philips on the 16th and that two days later the citizens had elected Hassell as the new Commander.

Peter Hassell who could not understand Dutch, wrote to the directors to inform them that Philips, of whom the population was very bitter, had been dismissed on June 16th, 1736, and that the citizens had elected him as Commander, which he had accepted against his wishes. Others made complaints as well. Philips treated the civilians with caning and abusive language and conducted himself as a Nero. William Richardson one of the wealthiest planters declared that Philips had cursed him out and threatened him. Even the Commander of St. Kitts, Gilbert Fleming, got involved and considered Philips a victim of his duties in a letter to the Council of St. Maarten dated July 13th, 1736.

After laying his case before the directors of the West India Company Philips was sent back to St. Maarten as Commander. He arrived back there on July 22nd, 1737 after an eventful trip. Together with Isaac Faesch he left Holland on the “Oostwaart” with Captain Roelf Alders. A Spanish coast guard ship boarded the “Oostwaart” close to St. Eustatius. The captain robbed both commanders and kept them for two days on his ship. After that he forced them to transfer to the frigate “Triumphant” with Captain Don Lopes D’Aviles. Who after two weeks left them on shore at Hispaniola, thirty miles from Santo Domingo with no other provisions than a bottle of wine and three biscuits, even letting them without a clean shirt, while at the same time the Spanish sailors were walking around with the stolen linen clothing. Faesch landed there in shirt and linen pants but without shoes and Philips in an old jacket. The Governor Don Alfonso de Castro y Maza did not treat them very well. But after the States General heard about it and they complained to Spain the two were allowed to leave and via St. Kitts they arrived on Statia on June 24th, 1737.

In the meantime, St. Maarten had lost its direct rule. Hassell and his rebels were commanded three times to come to Statia but they refused. Only when they heard that a Man-of War was coming from Curacao they went and surrendered to the authorities on Statia.

John Philips had been given instructions that he should not impose corporal punishment on the rebels. He appointed a new council and started a civil case which dragged on until a decision was made on February 24th, 1744 which gave some compensation to Philips for his losses but not very much.

John Philips must have had friends on the island as when he died in 1746 he was buried on the ruins of the old church in the Little Bay cemetery in a regular but still impressive tomb which still stands there even today. His antagonist Peter Hassell struggled from one crisis into the other. His bad temper was blamed on his “old age”. On March 27th, 1752 he ran into a problem with Commander Abraham Heyliger who condemned Hassell to be imprisoned and to be brought to the place where Justice was usually carried out and for him to be given lashes and branded with the branding iron, banished from the jurisdiction for 99 years with confiscation of all his goods and property and by provision that he would have to stay in prison until God (or the devil) called him home. After a petition from his wife and children and an apology from his part his sentence was reduced to a fine of 400 pesos. He died before November 8th, 1757 as on that date there is a conflict between his heirs.

A nice view of part of the lovely town of Philipsburg in its former glory days.

Commander John Philips had brought St. Maarten to an autonomous island and a large measure of prosperity. There is much more which can be said but space does not allow all for this article. However, from the trials and tribulations he went through for St. Maarten and the alternatives he had for a quiet life on his estate in Scotland you must admit that this Scotsman loved his new home , the island of St. Maarten.

Will Johnson

Postcard by Guy Hodge with Michel Deher overlooking the beautiful town named after Commander John Philips (1733-1746).